In this guest post, Project Q Researcher Yatharth Pandey examines AUKUS, Australia’s strategic positioning in the Indo-Pacific, and the role of emerging technologies within the context of the AUKUS agreement.

Great power competition in the Indo-Pacific between the United States and China is intensifying along economic, technological, strategic, and diplomatic lines. Australia, straddling the Indian and Pacific Oceans, holds a key position amidst this competition. The AUKUS national security partnership, the largest and most important defense and security partnership between Australia, United Kingdom, and United States in recent times was enacted in September 2021 and it added a major component to geopolitics and national security in the region and presented Australia with a golden opportunity to reach national security goals which it had long desired. Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese describes it as a “partnership that will promote a free and stable Indo-Pacific.” The emerging technologies that Australia is set to obtain across the AUKUS agreement can transform defense and security planning in the Indo-Pacific and re-shape collaboration efforts with its allies in the region. While much of the attention towards the agreement is focused on Australia acquiring its first nuclear submarines, technological innovation and growth in various defense and national security sectors outlined in the agreement could stand as the more substantial aim of AUKUS that would result in tangible progress for the national security and defense goals paramount to Australia.

The AUKUS agreement and its geopolitical gamesmanship has overshadowed the potential of emerging technologies across many national security and defense sectors across both pillars. Collaboration between the United States, Australia, and the United Kingdom can result in streamlining processes to obtain key technologies and reach key national security and defense objectives with both pillars. Pillar I’s objective is to deliver nuclear powered submarines to Australia, thus enhancing naval security goals which have eluded Australia while helping it achieve milestones in naval security. Pillar II consists of provisions to acquire additional emerging technologies for the three nations to collaborate on a number of advanced military objectives to enhance national security goals in the Indo-Pacific. While Pillar I has captured many headlines with its nuclear submarines, Pillar II’s promise for driving advanced capabilities in defense by acquiring emerging technologies across various workstreams in national security presents an opportunity for Australia to bolster its defense industry. Although many details about the progress of the initiatives described in each pillar remain classified, public statements offered by each of the governments help in regards to understanding their priorities across all parts of the agreement.

Pillar I Emerging Technologies

Adding nuclear submarines would be a significant upgrade in Australia’s naval arsenal over the aging Collins class of submarines. As per the agreement, eight SSNs (nuclear attack submarines) are to be supplied to Australia by the 2050s with a combination of Virginia class submarines purchased from the United States and AUKUS class submarines built in Adelaide’s shipyard and the United Kingdom. Australia’s military hopes to have at least two Virginia class SSNs that have been purchased from the United States by the 2030s, and one built on shore. This is in addition to five AUKUS class submarines that would be designed with assistance from the Royal Navy and built in Australia. Pillar I is forecasted to compromise seven percent of Australia’s defense budget and increase defense spending to 2.2% of the national GDP. This would also make Australia the first non-nuclear nation to acquire nuclear submarines.

The technological angle of the AUKUS class submarines has also been uncovered further with Australia’s Submarine Agency Director: General Jonathan Mead providing additional details. He claims there will be a more powerful reactor, enhanced surveillance capabilities, and increased capabilities for special forces operations. The submarines are expected to be heavier and have more firepower than the Virginia class according to Mead. The submarines will incorporate U.S based submarine technology including propulsion plant systems and a common vertical launch system. In addition, Australia aims eliminate the capability gap among its workforce to operate the submarines, and the United States is continuing to assist in this by training and graduating 50 nuclear operators and 50 submarine combat operators, increasing the workforce qualified to operate them in Australia.

Despite lofty promises and cutting-edge technology for Pillar I advertised by American and Australian leaders, there remains many questions of the timeline for the planned submarine’s objectives and emerging technologies to be realized. Concerns of the Virginia class submarines rising costs continue to concern Australian taxpayers and policymakers while fears that a change of administration in the United States could divert priorities from Australia leave serious doubts about Pillar I’s goals being fulfilled on its predicted timeline. According to the U.S Congressional Budget Office, construction of Virginia class submarines can take up to nine years to construct and there are doubts it can produce enough of these submarines for the U.S military. Supply chain issues further complicate emerging technologies in nuclear submarines, and public pressure continues to mount on the Australian side as rising costs up to $368 billion AUD over the next three decades are projected to be spent on the AUKUS submarines.

Pillar II Emerging technologies

While Pillar I’s promises could prove to be unfulfilled for Australia’s national security and naval defense plans due to the aforementioned concerns, Pillar II’s benefits could prove more beneficial in the long run with its concrete plans of acquiring additional technologies and cooperating with the United States and United Kingdom’s defense industries to boost Australia’s technological prowess in its region. In 2021, the agreement’s official wording was that it aimed to “enhance our joint capabilities and interoperability” in regards to defense and national security objectives in “cyber capabilities, AI, quantum technologies, and undersea capabilities”. These were later expanded on a revised edition in March of 2023, when hypersonic capabilities, innovation, information sharing, and electronic warfare. Pillar II is a boon for Australia’s national security goals as the technology gap with the U.S and U.K can be narrowed as the nations increased cooperation aims to gain the technological upper hand against rivals in the Indo-Pacific. These objectives are ambitious in scope and the emerging technologies that could come out of these would vault Australia’s defense industry’s into heights the government could have only dreamed of only a few years prior, and in order to accomplish those goals many technological leaps would have to be made in the workstreams listed in Pillar II to achieve strategic and technological dominance in the Indo-Pacific.

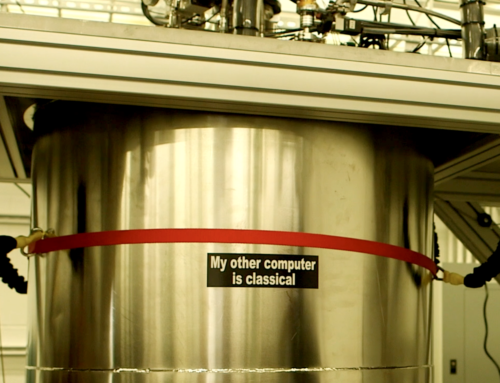

For example, cyber technologies in many world militaries are advancing at a rapid rate to keep up with geopolitical realities, and Australia is no exception with key advancements in communication and operations systems being prioritized. This workstream would tie into Pillar I with naval communications technologies improving the effectiveness of the planned AUKUS class submarines. Artificial Intelligence (AI) technologies have been mentioned as a key goal both to acquire and to defend against from threats. These advancements include AI algorithms on P-8A maritime patrol aircraft used to detect undersea submarine activity, an advancement that is critical for undersea advancements in detecting and stopping vessels as submarine technology grows stronger, which is important as China and Russia have recently invested in new technologies including improved sensor and quieting technologies and deploying unmanned vehicles. All countries have said they are collaborating on precision targeting, intelligence, and surveillance by using AI algorithms. These technologies are sure to revolutionize the national security and defense sector and it is critical that Australia keeps up in this regard. This was showcased within AUKUS in May 2023 when the United Kingdom hosted the first AI and autonomy trial in a demonstration. Quantum technologies have also been a core component, and AUKUS hopes to integrate them with military capabilities. Examples of this include additional stealth in undersea campaigns or assistance on alternate options for Global Positioning System (GPS). These are compiled in the AUKUS Quantum Arrangement initiative (AQuA) to coordinate quantum developments between all three nations. It’s also an additional example of Australia’s burgeoning quantum industry which ranks fifth in the world in quantum computing patents. $18.4 million AUD has been awarded to the University of Sydney’s Quantum Australia Centre in hopes to advance quantum technology and research, raise Australia into the world’s leading quantum research markets and hopes to compete with China in this sector.

In addition to the all-encompassing fields of cyber, AI, and quantum, Pillar II offers Australia the chance to pursue technological advances in alternate national security and defense streams. Hyper and counter hypersonic missiles developed by U.S DoD aim to be compatible with Australia’s defense arsenal through increased collaboration. As China and Russia have already been testing hypersonic missiles with the capability to deploy conventional weapons, Australia’s acquisition of the technology could make it a powerful player in the Asia Pacific. Additional developments in Pillar II’s scope such as electronic warfare technologies with the U.S Air Force Aircraft Wedgetail (an early warning system for undersea weapons) and the advancement of autonomous underwater vehicles are a boon for naval advancement. Innovation and Information sharing initiatives also have the potential to enhance cooperation between the three nations to share intelligence in a more efficient manner as a measure of deterrence and integrate innovative technologies in wargaming scenarios.

Takeaways regarding AUKUS emerging technologies

Pillar II of AUKUS is seen by many to be more reasonable to attain and promises greater technological innovation in a feasible manner. This is despite having many workstreams that advocate for technology and innovation that could be barracked by supply chain issues, bureaucracy, and changes in administration blocking them. Pillar I’s nuclear submarines, while huge for naval power, still are perceived to be far off in much of the public’s eyes due to steep costs, supply chain issues, and the extended timeline required to assemble them. Pillar II in contrast can be revolutionary for all three nations, as technological cooperation in its listed workstreams may end up having a more tangible effect than Pillar I on defense and national security policy. Prior defense agreements have been hamstrung by governmental leaders refusing to let experts in the field lead the charge in advancing technological sectors and instead slowly letting agreements fizzle out without much fanfare, so the architects behind many of Pillar II’s advancements must be careful to lead from the bottom up to foster technological growth and collaboration. To develop technologies in all AUKUS pillar II workstreams, the three nations need to maintain strong collaborative efforts in acquiring and developing many of the technological advances in all workstreams as well addressing any logistical differences within the three nations so progress is streamlined. While Pillar I’s feasibility questions continue to mount, advancements across Pillar II’s workstreams can fulfill many of the goals of the AUKUS agreement and can prove significant in addressing critical junctures of surveillance, intelligence, under-sea warfare, and threat prevention, sectors which Australia is primed to be a force in given sound collaboration efforts and effective leadership by experts are taken to ensure innovation in strategic technologies in the Indo-Pacific’s growing global power competition.

About the Author

Yatharth Pandey is an American master’s candidate in Security Policy Studies at George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs. He partook in a semester exchange program at the University of Sydney as part of the Elliott School Graduate Exchange Program. While in Sydney, he also worked as a research assistant at the Centre of International Security Studies under Professor James Der Derian. Prior to this role, he interned with the United States Senate Foreign Relations Committee and worked as a terrorism research analyst at the Terrorism, Transnational Crime, and Corruption Center. He holds a Bachelor’s degree from George Mason University in government and international politics. He is passionate in tackling issues involving transnational security, nuclear security, geopolitics in the Asia-Pacific, and energy security.

Leave a Reply