Friday morning saw of the best minds of a generation or two of IR scholarship, smartly dressed but nonetheless jetlagged, dragging themselves to Sydney’s Wharf 6 to catch a ferry across the magnificent harbor to Q Station in Manly. Scholars from across the world and the field sat top deck alongside tourists and commuters, familiarizing themselves with both each other and some of the world’s best manmade and natural scenery.

Pulling into the small dock at Q Station, participants made their way uphill, past impressive etchings left in the sandstone bluff by some of the facility’s former guests. Upon reaching the top, the group was welcomed to the quarantine ward’s hospital, since re-purposed as a conference venue, by a fantastic view of the harbor and some much-needed coffee.

An etching left by the crew of the RMS Lusitania during their quarantine stay in 1895. (Photograph: Ben Foldy)

The conference’s participants assembled, it was time for the first panel of the conference and the day. But first, Gadigal Elder Uncle Chicka Madden, in his capacity as Secretary of the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council, welcomed the participants onto the Eori land that Sydney and its surroundings were built on. He explained some of the history of the land and its people, but spoke as well of the present he is privy to in his work with the National Centre for Indigenous Excellence and the Aboriginal Medical Service.

Uncle Charles “Chicka” Madden, Gadigal elder, welcoming Q Symposium participants to Eori land as CISS Director James Der Derian looks on. (Photo: Jose Torrealba)

With considerations of past and present complete, it was time to look towards the future. Professor Duncan Ivison, Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at the University of Sydney, spoke of the conference as a testament to University of Sydney’s recognized position as a leader in global security studies and willingness to look towards the horizon of global security and social science. Centre of International Security Studies director James Der Derian then took to the floor, thanking the Dean and the Carnegie Corporation of New York for their generous support of the Q vision.

Der Derian then spoke to the question at the tip of everyone’s tongue- just what exactly was the Q vision? He told how the idea began when he was working in Copenhagen, a city whose native son, Niels Bohr, was held in such high esteem that growing up I was regaled with stories of ordinary Copenhagen folk bowing at the mention of the great man’s name during my grandfather’s sabbatical spent doing research at Bohr’s Institute for Theoretical Physics.

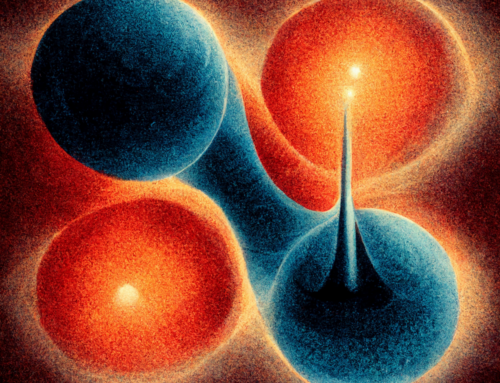

Such reverence came from Bohr’s role in developing, theorizing, and bringing together a research program—the so-called “Copenhagen” interpretation of quantum mechanics which completely re-imagined the laws underpinning the physical universe. And as important as Bohr’s role was as a theorist in his own right, he was perhaps an even greater collaborator. The Copenhagen Interpretation came not just from the individual genius of Bohr and Werner Heisenberg, but was theorized, defended, re-evaluated and ironed out over a number of years by a golden generation of scientists from across Europe and North America, drawn regularly to venues like Bohr’s Copenhagen Institute and gatherings like the famous Solvay Conference of 1927.

Attendees to the Fifth Solvay International Conference, held in 1927. Attendees’ names are visible along the bottom of the picture. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

CISS and the Q Symposium are pursuing a similar end. Citing his one-time mentor Charles Taylor, Der Derian explained to participants that we define our identities in dialogue. At the heart of the Q Symposium was a desire for the same kind of dialogical spirit through which a critical mass of top scholars could re-theorize the security universe. By bringing together practitioners, theorists and observers from politics, security, physics, computer sciences, biology and more, the possibility, impact and desirability of developing a quantum interpretation of social science could be discussed from a number of vantage points.

Der Derian then answered an unasked follow-up: why now? Understandings of quantum mechanics have been theoretically described since the 1920s, and while such pioneering quantum theorizing was largely confined to the abstract, quantum principles have been steadily accumulating experimental evidence showing it to be the most predictive and verifiable interpretation of our physical world. Nonetheless, social sciences, and particularly those associated with international relations, often seem firmly wedded to a somewhat Newtonian notion of cause and effect.

What a quantum interpretation could potentially offer is a means to better understand a world that more and more often seems to defy the predictions of conventional security studies. As quantum’s turn in physics shifted the emphasis from theorizing the relatively orderly interactions of microphysical objects (i.e. an apple dropped from a tree falls to the earth) to the unpredictable, “weird” aspects of atomic activity at the nanophysical level, so too could a quantum IR potentially provide a handle to a world in which threats come from the atomistic elements of world security.

In a world where an epidemic vector can pass through three or four major airports in a day, where governments develop computers based on quantum principles in attempts to achieve an omnipresent surveillance capability over billions of independently-acting individuals, should we not train ourselves like physicists to understand that there may be a set of laws different for the micro-world of politics than those governing the macro?

Secondly, the implications of quantum mechanics for international security are moving towards becoming acutely real. Among the documents leaked by Edward Snowden was confirmation that the NSA has allocated $79.7 million dollars towards research and development of a “cryptologically useful” quantum computer able to assist in their efforts to “Own the Net”. Such a computer, if possible, could harness quantum mechanics and far exceed the capabilities of even the most advanced binary computers, literally expanding the universe of computational possibilities for information security (encryption/decryption, biometrics), biosecurity (pharmacology, biology, again biometrics) and other security-related fields.

The design of the conference aimed to draw on two other quantum insights as well. The first was the notion of complementarity. The concept was originally proposed by Bohr as a way to reconcile the observable fact that objects exhibit different properties depending on the manner in which they are observed. Light can exhibit particle or wave functions, depending on the observational apparatus.

But an experiment cannot capture both functions simultaneously. The functions then are complementary, with both observations in conjunction, though made separately, able to describe a more complete range of properties. A complementarity principle in security studies could allow for research to draw on differing ontological suppositions and disciplines in order to yield more complete understandings of international security. The formalistic boundaries of matter/ideal, states and non-states, levels of analysis and the like can be more apt to describe our political universe than those clinging to more classical concepts.

The second, related to the first, is that the act of observation itself shapes that which is “under” observation. An experimental apparatus cannot be separated from the universe it observes. To this end, Der Derian announced to Q Symposium participants that a film crew would be documenting the entire conference, to be produced into a documentary with generous support from the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

And with that, discussion of a new quantum IR began.

[…] welcomes and opening remarks set the tone, Friday’s first panel took the baton from the groundbreaking research presented in […]