Susannah Lai

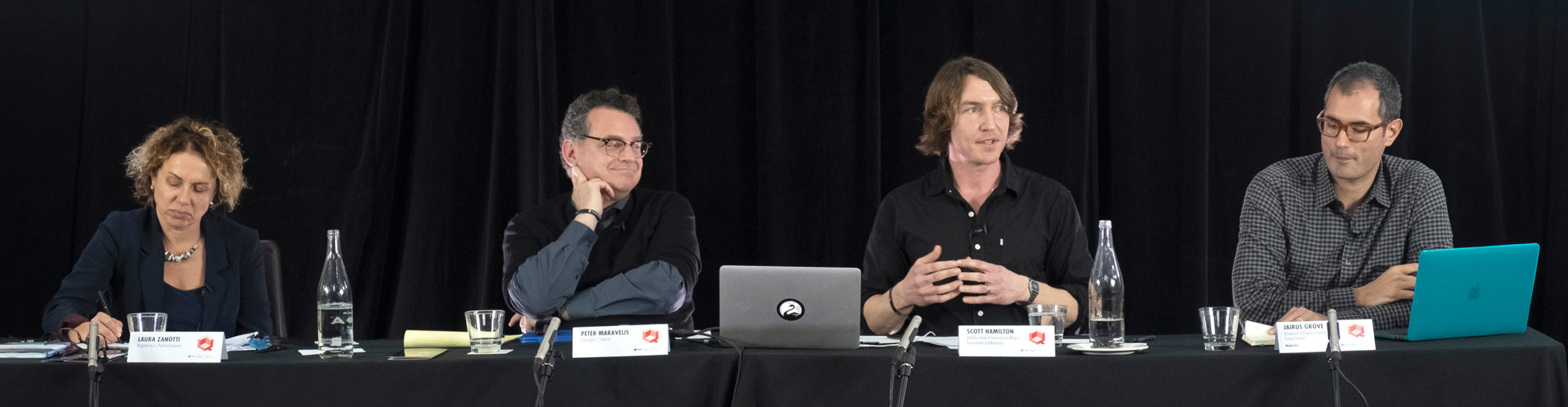

The next panel took a turn for the philosophical, asking what ‘quantum metaphysics’ might look like, or if there even is such a thing. The speakers for this panel were Professor Laura Zanotti, Mr. Peter Maravelis, Dr Scott Hamilton, chaired by Associate Professor Jairus Grove. As might be expected from such a philosophical subject, the individual focus of each speaker varied greatly; from the already-adopted physics models in metaphysics and what quantum might offer it, to observing the impact of technology on life and philosophy, to defining metaphysics as it is currently understood versus shifting to a new paradigm.

The first speaker was Professor Laura Zanotti of Virginia Tech, who focused on what creating a ‘quantum’ conception of metaphysics might mean. Her talk explored if it would be a feasible way to understand how the world around us is comprehended and if this new conceptualization would add anything to our current understanding of metaphysics. She started by asking what it would mean to organize the world as a ‘quantum’ place and mused on the current intersecting models of physics and metaphysics, the conceptualization of the world in terms of a structure, masses and momentum, as well the cartesian interpretation of mind over matter, that is to say, the acceptance of dualism regarding mind and matter being equal in their affect.

Professor Zanotti then reflected on metaphysical philosophy relating to change, linking it to the Newtonian concepts of the action of force upon objects and applying that concept to postulate and explore what it would mean for a human concept. She explained that ‘power’ under this interpretation is about the influence or impact of forces on objects which move them away from what they may naturally be inclined to do. The interrelation of metaphysics and the ‘hard sciences’ is not always immediately apparent, but the move from this purely ‘Newtonian’, deterministic view of metaphysics to a ‘quantum’ view is a far less certain conception. This is because quantum particles are not ‘atomic’ or individual in the same way that metaphysical objects are in the conventional mode of thought and deterministic metaphysical theory is challenged when related to the quantum-mechanical uncertainty principle. The latter difficulty inspired Albert Einstein to propose alternative theories, such as the hidden-variable theory, to retain determinism even under the effect of an uncertainty principle.

She further expounded on the consequences of accepting a mode of ‘quantum’ metaphysical theory, asking what would happen when conceptualizing another quantum-mechanical property—that of quantum entanglement, particularly with relation to social relationships and how they are thought of. Professor Zanotti explained that under this interpretation, people are ‘entangled’ in their ontological events, and therefore they all affect one another in the way they engage with said ontological events. This follows more closely the ‘engaged theory’ framework for understanding social complexities.

Furthermore, she said, there is a general tendency to imagine that the world is very homogenous, so if one blueprint were to be developed for a specific society, it would be similarly applicable to all. However, the world is not like this. It is a very complex place, with multiple forces and influences working differently to various degrees on different societies and places. This creates an extremely varied environment that precludes thoughts and structures applied successfully in one place, from guaranteeing successful or even similar results when applied to another. Unsurprisingly, Professor Zanotti heavily condemned this logic of ‘similarity’; it was not good to think this way, she warned, as it would only create problems when things did not go according to plan. Considering that this discussion was focused on social and political situations, this would imply heavy impacts and costs on human life in areas affected by such misjudgments. It was very Kantian, Professor Zanotti concluded, to speak of ‘unintended consequences’ relatively lightly, diminishing the severity and reality of those consequences in a way that would not be done if said consequences were visited upon the people that caused them.

The discussion took a turn from the theoretical with Mr Peter Maravelis, Events Director at City Lights bookstore in San Francisco, who first outlined the life of one Lawrence Ferlinghetti, the founder of said organization, before discussing the other situations that face his home city. He explained that Ferlinghetti, serving in the Navy in 1945, visted Nagasaki just a few weeks after the atomic bomb had hit the city. What he saw there changed him into a lifelong pacifist. When he returned home, he worked to deter any repeat of the destruction he had borne witness to, and in the course of his activities, which included being a prolific author and poet, he co-founded the bookshop City Lights, which evolved into a hotbed of revolutionary political ideas and drew people interested in changing society to congregate around the organization.

Fitting with Ferlinghetti’s populist ideals, City Lights was the first paperback bookshop; a much cheaper and more accessible form of publishing, which opened the world of literature to a greater audience, previously excluded by the prohibitive cost of books. Ferlinghetti also penned many essays and commentaries on various political and socio-economic issues, and was an early commentator on the topic of ‘virtual life’ and the internet. In keeping with the forward-thinking nature of the discourse fostered by City Lights, there is a current focus on quantum technology, making the comprehension of all its potential for society, good and bad, a top priority for the organization.

Mr Maravelis talked about San Francisco as a city overall. It was, he explained, a ‘tech-forward’, early adopter city, interested in any new technological solutions to problems, or even technological solutions to things that had, perhaps, not previously been problems. In terms of the political atmosphere of the city, Mr Maravelis explained it to be ‘liberal’ in ideals, although the reality is of course more complicated. As San Francisco has grown, spurred on by investment in technological start-ups and proximity to Silicon Valley, the cost of living in the city has sky-rocketed. This has led to the gentrification of neighborhoods and has also resulted in substantial and still growing homelessness.

The root of the problem, asserted Mr Maravelis, was that while capitalism fundamentally relies on the presence of customers, the individuals at the ‘top’, at least in the United State’s brand of capitalism, do not truly ‘give back’ to the community. Regarding the practice of philanthropy, he was of the opinion that it is fundamentally self-centered one way or another, either by only promoting the donor’s particular beliefs and interests, or by forwarding other interests that the donor might have; therefore, still benefiting the donor either by furthering their moral belief system, or by providing some indirect material advantage.

There are lessons that can be taken from San Francisco. ‘Tech culture’ can cause problems, but society as a whole can work to fix these problems. Mr Maravelis supports the idea of a ‘fluid ontology’, relaxing the conception of the standing any individual should have in a system, and embracing engagement in technological developments, not merely as a consumer, but as a citizen. If this was the approach taken, Mr Maravelis entreated, would it not be eminently possible to make quantum technology equitable?

The last speaker for this panel, Dr Scott Hamilton of the Balsillie School of International Affairs, turned the discussion back to the theoretical, seeking to explain what metaphysics is, and its impact on society across various civilizations, as well as the changes and challenges a ‘quantum’ mode of thinking would pose. His first topic explained what metaphysics means, and how metaphysics has changed over the centuries to develop into the modern western metaphysical structures currently accepted around the world. While he acknowledged that other cultures had their own vastly varied metaphysical modes of thought, Dr Hamilton chose to focus on western metaphysical theories, in particular, those of Ancient Greece.

Dr Hamilton discussed the example of metaphysics in Ancient Greece, specifically what they thought of ‘causality’. In modern society, the widely adopted metaphysical model of causality is relatively simple: cause and effect, normally following the arrow of time. However, in Ancient Greece, there was a very different four-fold model. The four-fold model of causality was proposed by Aristotle and is an influential principle in Aristotelian thought. It had the stages of ‘matter’, or the ‘material form’ which looked at what material was used; ‘form’, or the ‘formal cause’ which looked at what design was used; ‘agent’, or ‘efficient cause’ which looked at by what means it was transformed; and finally, the ‘end’, or ‘final cause’ which looked at what purpose something had. Summarized, and loosely so, it examined the ‘what’, ‘how’, ‘who’ and ‘why’ of any object. This is, of course, vastly different from how causality is perceived today.

This was how, Dr Hamilton said, metaphysics presented different ways of understanding the world. As for the current schools of thought in metaphysics, he asserts that models such as ‘Newtonian’ and ‘Cartesian’ are used, with the accompanying conceptions of things being ‘atomic’ and the ‘eye of subjectivity’. He particularly focused on the idea of the ‘eye of subjectivity’, saying that the idea of perspective, particularly in art, did not exist before the concept of the ‘individual eye’ was understood. He also suggested that part of the revolution that happened with the advent of this conception was the rise of individualism and that prior to that, people had generally thought of themselves as being a part of a community rather than as a sovereign entity.

Quantum, Dr Hamilton declared, will change all of this. It will challenge all the conceptions currently held. The notion of ‘atomic’ granularity will be overthrown along with various notions of subjectivity. This is of concern, he warned, because people are not able to choose their own ‘metaphysical background’, which is dictated by the society and culture they exist within, and forms their basic way of thinking as well as processing and absorbing knowledge. It necessarily follows that in order to function in society, an individual needs to follow the dominant metaphysical axioms. Considering this, it would behoove society at large to carefully consider any changes that would be made at a cultural level in adopting new metaphysical axioms.

In the case of the potential form of a ‘quantum’ metaphysical axiom, Dr Hamilton postulated that there would be a ‘quantum paradox’ in the matter of self-reflection, asserting that looking upon the self would simply result in an infinite feedback loop of subjective self-reflection. This, though grave, would not be the worst possible outcome of blindly adopting this new mode of thinking, he warned, as it was possible that the ‘eye of subjectivity’ would be lost, and along with it, other theories of individualism. This would have many implications, including possibly losing a great deal of ideas of liberalism about individual rights, according to Dr Hamilton. It would mean adopting a new ‘formulation of being’. But would such a complex and little understood set of ideas be beneficial or even comparable to the current metaphysical ideas that are based on mathematical formulations? Dr Hamilton suggested that the adoption of a ‘quantum metaphysics’ should wait until these questions can be cogently answered.

Leave a Reply