Niander Wallace pondering the creation of life altering new technologies in Blade Runner 2049. Image credit: Sony Pictures/Warner Brothers.

Alexander Vipond

Researchers at MIT have undertaken the world’s largest survey on the moral preferences of people to different variations of the trolley problem. The trolley problem’s basic premise is this: a vehicle is about to have an unavoidable accident and the driver must make a choice as to who or what the vehicle hits e.g. swerve right and hit a young man or swerve left and hit two old people?

Edmond Awad and his team collected over 39.6 million decisions from 233 countries through a specially designed mobile game and website. The game and website asked participants to weigh the ethical issues of different versions of the trolley problem according to 9 life indicators (which can be seen in infographic b below). Previously, most studies have relied on single indicators such as a preference for saving many lives over one rather than attempting to look at the complex interrelationships of multiple indicators. From the responses, the researchers were able to discern large scale patterns and trends from 130 of the countries to identify peoples’ key ethical preferences for the preservation of human life.

Hierarchical clusters of countries based on average marginal causal effect. One hundred and thirty countries with at least 100 respondents were selected. The three colours of the dendrogram branches represent three large clusters—Western, Eastern, and Southern. Country names are coloured according to the Inglehart–Welzel Cultural Map 2010–2014. Image Credit: Awad et al in Nature, ISSN 1476-4687.

They discovered three different ethical worldviews: The Eastern, the Southern and the Western (as displayed in infographic A). These groups agreed on some basic principles and diverged on others. They shared three major preferences. That young people should be spared over others, that many people should be spared over a few and that humans should be spared over other species. These preferences traversed different cultural, economic, political and religious boundaries.

However, as you can see in the radar plots of infographic b, Eastern, Southern and Western views also express sharply different preferences across the spectrum of the nine life indicators. The Western view skews towards saving the young, the many and taking no action at all, giving the choice to chance. The Eastern view skews towards saving the lawful, humans and pedestrians whilst the Southern view prioritises women, the young and high-status individuals.

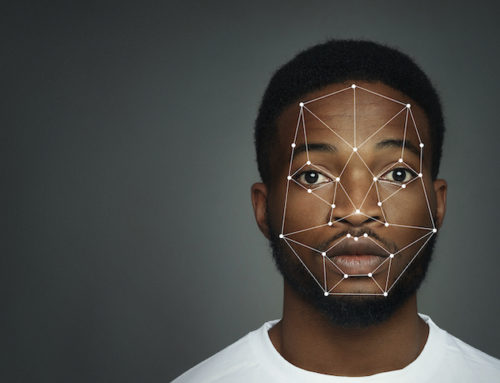

Machines are on the verge of being programmed to make life-altering choices, a turning point in history. The questions Awad’s team raise over whether universal machine ethics are possible and whether societies can reach consensus over the use of intelligent technologies are a crucial step in discussing what sort of world we want to live in as we undergo the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

While the world is focused on the threat of killer machines on the battlefield, machine decision-making will pose challenges in times of war and peace. This research tests the limits of universal standards as country specific preferences emerge from the complexity of weighing multiple factors. The scalability of new intelligent technologies may be limited by their adaptability to different cultural environments with varying ethical standards. Geo-strategic tensions and ethical dilemmas over who has the power to control these choices, the diversity of datasets used to make technology and the research used to justify life altering choices will affect company, consumer and government.

For example, moving to a different country in the future may mean moving to a set of new technological moral compasses which will have different criteria, levels of access and personalisation, dependent on the rules of the society.

The Moral Machine experiment is only a snapshot in time; a poll of preferences that remains fluid. Ethical standards will require sensible discussion and update periods to reflect changes in the community. Awad notes that the situations presented rely on 100 per cent certainty of the events occurring and 100 per cent certainty of recognising the targets. In the real world there is a much greater level of uncertainty in these processes.

Beyond this lies the extreme technological challenge for engineers and scientists of how to weigh the vast array of preferences with any semblance of granularity. Can your car accurately evaluate someone’s societal status in the 3.2 seconds before a crash? That technology has yet to arrive. However, in some countries the autonomous car might link with the mobile phones of surrounding pedestrians and choose the person with the lowest social credit score by proxy.

As intelligent and networked technologies continue to develop and impact our lives they will increasingly become imbued with formalised versions of the rules that govern our societies. The collective may gain power over the individual. What we have previously left to chance and split-second decision making, we will now expect to be pre-programmed with precision into machines. As Awad’s research shows countries and communities need to start national and regional conversations about what should be delegable to an autonomous machine and how it is operated, before it is decided for them.

Leave a Reply