Investors beware: Futurist technology stock is low-hanging fruit for any short-selling investment firm prepared to deploy a ‘special’ kind of rhetoric and persuasion.

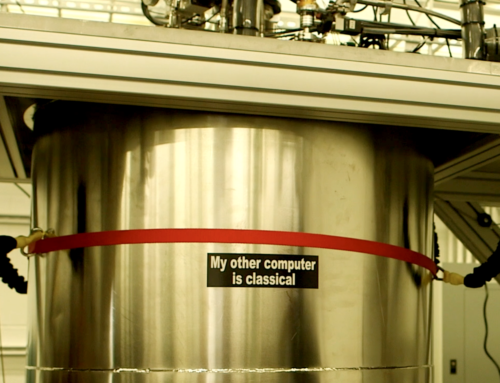

On 3rd May, Scorpion Capital released a damming report, accusing the world’s only publicly-listed quantum computing enterprise, IonQ, of perpetrating a massive fraud upon the public and misleading their investors. Three days later, IonQ’s share price was down almost 20% and Scorpion had made a lot of money. According to the report, IonQ’s entire quantum computing project was vapourware, their financing a shell-game, and their CEO a clueless braggadocio. Scorpion’s 183-page document presented an open and shut case: IonQ’s quantum computer was a hoax; investors better get out while the going was good.

I’ve read the report in its entirety and scrutinized the evidence used to support its claims. I’m in no position, however, to address every one of the issues raised by Scorpion Capital. An effort was made to seek information from IonQ’s founders, who told me, “we cannot comment on the content” of the report and referred me to their public response.

Please note, this does not pretend to be a defense of IonQ, per se. Instead, I want to discuss the situation more broadly. The issue I wish to address in this essay is the predicament any publicly listed company dealing with prospective, novel, and uncharted technology will find itself in: utterly exposed to the kind of tactical short-selling undertaken by Scorpion Capital. In other words, early investors in futurist technology will always need to factor-in the kind of aggressive undermining of their positions by investment firms with a vested interest in profiting from what is, by definition, low-hanging fruit. Elon Musk has made this point on multiple platforms at various stages of his career as an entrepreneur.

In a nutshell, here’s how Scorpion Capital (or any similar short-selling oriented firm) can make ‘easy money’:

- Identify a publicly traded company dealing exclusively with a futurist technology;

- Establish that little or no progress has been made concerning said technology to date, by any entity in the space;

- Use the industrywide lack of technological breakthrough to support claims that the specific company is perpetrating a fraud.

Before proceeding further with a discussion of Scorpion Capital’s methodology, I want to reiterate: I am not defending IonQ. I have no way of knowing, for certain, the status of their operations, financing, or technical development. What I can say, however, is whatever fraud IonQ may or may not be perpetrating was in no way proven, let alone established, by the Scorpion report. The Scorpion report is an artful and compelling work of rhetoric and persuasion, not a reasonable presentation of balanced research. The report smacked of Cicero’s Philippicae instead of KPMG – i.e., the art of the defense attorney and nothing of the judge. Whatever ethical position one might take, this approach is perfectly understandable and highly rational given Scorpion’s objective to influence market sentiment regarding IonQ so they can make money.

To make the case that any publicly listed company dealing with prospective, novel, and uncharted technology finds itself utterly exposed, let me explain the deconstructive method of analysis I use to carefully examine Scorpion’s claims. Once you understand Scorpion’s strategy and effect, it will become more apparent that any company dealing in truly innovative research lives by the market and potentially dies by the market.

Deconstructive Argument Analysis

The first thing I did was read through the report and itemize all the substantive claims made by Scorpion Capital. There were 30 such claims. I then tabled the evidence cited in support of each of the 30 claims. Next, I examined the claims and noted they fell into one of two categories:

- Claims of fraud/impropriety; and

- Claims of poor performance.

I then examined the evidence for these two categories of claims and noted that, in many instances, claims of fraud/impropriety were being substantiated by evidence of poor performance. This is contrary to the expectation that claims of fraud/impropriety would be substantiated by evidence of fraud/impropriety. Let’s call this ‘evidentiary comingling.’

Finally, I scrutinized the evidence of poor performance and noted that, in many instances, the evidence related to the poor performance of the ‘technology,’ writ large, not IonQ’s technology, specifically. This is contrary to the expectation that allusions to evidence of IonQ’s poor performance would allude to actual instances of IonQ-specific poor performance. Let’s call this ‘evidentiary conversion.’ To summarize, here is the how Scorpion Capital’s argument (or rhetoric) works:

- Convert evidence of industrywide poor performance into IonQ-specific poor performance; next,

- Make a claim of fraud/impropriety on the part of IonQ; then,

- Support the claim of fraud/impropriety with ‘converted’ evidence of IonQ-specific poor performance; and, therefore,

- Claim to have ‘established’ fraud/impropriety on the part of IonQ.

If the report was presented in as ham-fisted a manner as my analysis reveals, it could hardly be considered an artful and compelling work of rhetoric and persuasion. The style, in particular, the sequential delivery of the report’s information, is therefore a necessary dimension of its effectiveness; or, as noted deconstructionist Jacques Derrida once put it, style is the author’s will to power in the text.

The first 20 or so pages of the report are nothing but claims of fraud/impropriety supported by ‘converted’ evidence. It is not until pages 20 to 40 that you come to see that the ‘converted’ evidence is derived from evidence of poor performance (not evidence of fraud/impropriety, per se). Pages 40 to 60 present superficial, speculative, and weak evidence of fraud/impropriety (which serve to bolster the prior claims which were themselves supported by ‘converted’ evidence). It is not until pages 60 to 150 that you, finally, come to see how the evidence for poor performance is ‘converted’ from industrywide poor performance into IonQ-specific poor performance. The final pages (150 to 183) deal with further speculations which have little to do with either poor performance (industrywide or otherwise) or fraud/impropriety, being instead a repetitive variety of ad hominem. In other words, the argument is presented in almost the inverse sequence to the order in which the logic of the argument is derived. On the one hand, you could say Scorpion Capital’s report is a manipulated form of syllogistic reasoning. On the other hand, it is 183-pages that read like the question, “when did you stop beating your wife”? Let me provide some specific examples:

The Great ‘Computer Hoax’

The Scorpion report is titled:

“The “World’s Most Powerful Quantum Computer” Is a Hoax…”

Let’s examine one element of Scorpion’s evidence that IonQ’s quantum computer is a hoax. Scorpion claims they spoke to ‘insiders’ who confirm the machine doesn’t exist. Scorpion indicates they spoke with a senior executive of 1Qbit (a listed IonQ partner). Based upon their interview with the executive, Scorpion writes, “he indicated that the machine “isn’t really real” for any type of production setting and has “way too much instability” and errors to be used on “mission critical tasks” …”

Let’s understand how this evidence was ‘converted.’ The full quote by the executive is:

“…apologies if this is well understood – using quantum computers in any type of production setting isn’t really real, so nobody’s using quantum computers beyond just experimenting with quantum devices.”

The comment with respect to “isn’t really real” doesn’t relate to IonQ’s machine, specifically, it is a remark concerning quantum computing, writ large.

Additionally, the executive states:

“… there are no mission-critical tasks you would ever ask a quantum computer to do because it’s just too early days for that, and there’s way too much instability in terms of errors that get introduced…”

Once more, the comment with respect to “way too much instability and errors to be used on mission critical tasks” doesn’t relate to IonQ’s machine, specifically, it is a remark concerning quantum computing, writ large.

Elsewhere, the Scorpion Capital report suggests the expert stated, “anybody tinkering” with IonQ’s device “isn’t really doing anything”; that the type of computation one can do with it is “trivial”; and that the machine is “not really useful.”

Let’s understand how this evidence was ‘converted.’ The full quote by the executive is:

“The way to think about this stuff is anybody who’s tinkering with the IonQ device in AWS or Azure Quantum isn’t really doing anything. That type of access or that type of computation in the cloud is, I mean, it’s trivial or just the nature of the work you’ve done. So, there’s no feedback necessarily. It’s not really useful…”

The comment with respect to “isn’t really doing anything” doesn’t relate to IonQ’s machine, specifically, it is a remark concerning the kind of access one has to quantum computers using cloud-based computation, writ large. When the executive says “tinkering” this is their description of cloud-based access, not their experience with IonQ’s machine, specifically. Finally, according to the executive, the something that is “not really useful,” is the cloud-based access to quantum computing, not IonQ’s machine, specifically.

There are many, many, such examples which illustrate the manner in which Scorpion Capital converts statements regarding industrywide poor performance into ‘evidence’ for IonQ-specific poor performance. Scorpion is not hiding their rhetorical conversion either, it’s right in their report and anyone can see how it is done if they take the time to read the final 100 or so pages.

Financial Fraud

Another aspect of Scorpion’s argument that IonQ is perpetrating fraud/impropriety is the claim that IonQ generates little or no meaningful revenue, and, yet, has advanced accounting bookings in excess of USD15M. In support of this claim, based upon interviews with an IonQ partnership executive, Scorpion writes:

“… “there’s no money involved in the current partnership” and “no money changing hands,” which suggests that despite the hype, IonQ can’t get anyone to even pay to use their “world’s leading” quantum computer.”

However, when you examine the complete statement made by the QCWare executive, you find they actually said:

“Right now, there’s no money involved in the current partnership we have… we bring the customer to you, IonQ, to run this, and so, you, IonQ, benefit by running this experiment and getting your name associated with the customer like a Goldman Sachs. That’s the kind of customer we would bring them. And, therefore, there’s no money changing hands between QCWare or IonQ in this partnership.”

Clearly, therefore, Scorpion’s evidentiary claim is a rhetorical distortion of the executive’s statement. There’s nothing untoward, or, unusual about “no money changing hands.” Instead, the arrangement is typical of the quantum computing industry, writ large, whereby established companies are invited to make use of the technology such that IonQ can accrue reputational capital based upon their association with Goldman Sachs. It’s not that “IonQ can’t get anyone to even pay.” Instead, it’s that the existing (and presumably satisfactory) arrangement is a non-financial quid pro quo.

In conclusion

Again, this piece should not be interpreted as an effort to exonerate IonQ. Instead, I merely aim to illustrate that the evidence that Scorpion provides to support their claims against IonQ is (in the main) of a very particular kind. It is ‘converted’ evidence to support an entirely different category of claim. Ideally, to make a compelling argument you ought to encounter:

Claim of variety A; supported by evidence of variety A.

The manipulated syllogistic from of which is:

Claim of variety A; supported by evidence of variety B.

What Scorpion Capital does, however, is something far more artful and compelling. Scorpion offers the “when did you stop beating your wife” form of argument:

Claim of variety A; supported by evidence of variety B; evidence of variety B introduced by sleight-of-hand from the evidence of variety C.

I offer my method of analysis so that anyone who decides to read Scorpion’s report can identify it for what it is, and critically interpret its findings. Moreover, I cite the Scorpion Capital report as an object lesson for any investor in innovative, futurist technology stock. Until said technology reports industry- or sector-wide confirmation of “breakthrough” and/or advance – i.e., so long as the sector, per se, remains prospective and uncharted – your stock represents low-hanging fruit for any short-selling investment firm prepared to deploy the kind of rhetoric and persuasion on full display across the Scorpion Capital report.

.

.

.

.

.

(Disclaimer: Project Q is supported by the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Sydney Quantum Academy and the University of Sydney. The Project does not receive funding from quantum or any other technology firms. As part of the Q Symposia and its documentary film, interviews have been conducted with quantum scientists from Google, Microsoft, Quintessence, IonQ, Q-CTRL and quantum research labs, which are available here)

Leave a Reply